There are few words as loadbearing in games as “like”. From games hoping to break through the noise on increasingly crowded storefront pages, to reviews and previews at sites hoping to disrupt doom scrolling, [game you and millions of others know here]-like has become one of the most common ways to onboard a prospective audience for a new experience.

While it can be a bit exhausting to see this particular description method everywhere, especially when it comes to terms like roguelikes, it’s hard to dispute the efficacy. In fact, this entire article and the interview it’s sharing wouldn’t exist if not for Citizen Sleeper creator Gareth Damian Martin sharing on Bluesky what they said might be the first Citizen Sleeper-like. In moments like this, I’m no better than anyone else — when the creator behind one of my favorite games says a new project might be the first “-like’ of their work, I’m going to do some investigating.

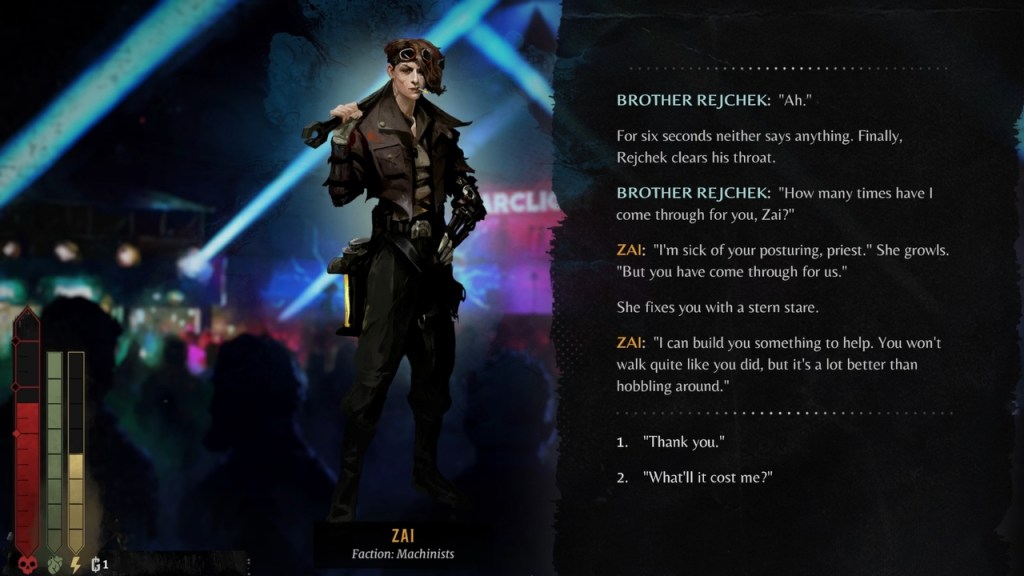

This particular investigation led me to Duskpunk, a dice-driven narrative RPG set in a steampunk world where bodies are turned into fuel, soldiers dodge the draft and certain death, fascists make everyone’s days miserable and, maybe, revolutions happen. The demo left me impressed with how it realized the setting Dredgeport as a cruel city where making it to tomorrow is a constant challenge. The full experience was no less enjoyable as I learned not only how deep the depravity of Dredgeport’s ruling class is, but also how strong the spirit and fight of its workers are through a mix of sharp writing, engaging sound design, sweaty skill checks and consequential decisions.

However, the most interesting part of this experience for me was how Duskpunk diverged from its most explicit inspiration, Citizen Sleeper. While the similarities are undeniable, especially around themes of agency and liberation, several design choices ensure creator James Patton’s work diverges from its inspirations and emerges as a uniquely thoughtful experience. I sat down with James to talk about these choices, in addition to his journey as a game developer, why he decided to market Duskpunk as a Citizen Sleeper-like, what makes a game immersive and the limits of “-like” as a descriptor.

You can find a lightly edited excerpt from the interview below. The full interview can be watched on YouTube.

Exalclaw: First, what was the decision process like for you marketing this game as a Sleeper-like? I’m understanding why it was an inspiration for you, but having an inspiration and then naming a game as an inspiration in your marketing, two different things. So, I was curious about that.

And then, what was the process like in trying to figure out what worked from Citizen Sleeper for Duskpunk versus what didn’t? How did you know what to pull from your inspiration that didn’t hurt the vision you had for Duskpunk as a whole?

James: Yeah, so the marketing thing… the main reason I picked Citizen Sleeper was it seemed like a good way to take my skills and turn them into a thing that was finished and saleable. But, the more I thought about it, the more I was like this makes total sense because Citizen Sleeper has made a bajillion dollars, right? It’s on Game Pass. I think it’s crossed a million players or something. It must at least have made, I think at least $300,000 or something. So I thought, my goal was like if I can hit 40K then I’m good. And that’s over the course of multiple years. So I thought if I can just have a tiny slice of that audience, then that already makes the numbers work out.

I think a lot of games, they try to stand on their own two feet and they don’t say we’re an X-like, but in this case, it made sense to me because I was like, well, there’s… it doesn’t seem like it because I think narrative games are quite… it’s like social media and Steam don’t really know how to send narrative games to narrative players. There’s some mismatch there unfortunately. But, I know that they’re there, so if I can just find them, then they will be interested in the game and will hopefully buy it. And so I thought that by calling it a Sleeper-like, and by sort of stressing the fact that it was Citizen Sleeper plus Dishonored, that’s two franchises where if one of them resonates, then you’re interested. And if they both resonate, you’re like oh, fantastic! It’s my jam or whatever.

It’s already kind of worked. It’s currently recouped about 40% of the total cost of production. So I think it will probably recoup its total value in a year or two, which is not where I was hoping for, but I think it’s respectable for a narrative game. But I think it would’ve been more successful with the backing of a publisher because I think if they had an existing audience and they had the marketing resources, then I think they could’ve really broken through to that group of players who’ve played Citizen Sleeper and loved it. I still think there’s tons of people who haven’t heard about it who would love it, but you know it’s difficult to reach them.

Exalclaw: Right.

James: And then to your second question about what worked and what didn’t when I sort of translated it over. So I think the dice mechanic in Citizen Sleeper is really interesting, where you roll the dice at the start of the day and then you spend them, but I really wanted to hone in on this idea of precarity and vulnerability and of always feeling like you’re pushing your luck. And then, that feeling of getting over a hump where you thought it was very difficult and then it turned out that if you just push hard enough, you could kind of get to the other side and then everything worked again. So rather than using the roll all the dice ahead of time system, I just replaced it for a standard you roll two D6 and you add your skill against a difficulty. It’s a very old-fashioned system. I literally borrowed it from game books from the 1980s. So it’s kind of the oldest and clunkiest skill check in existence.

But, I particularly wanted that because when I played some of those game books, two D6 has a bell-shaped distribution whereas if you roll one dice, it’s totally flat, and that meant that when you start the game, you’re on the bad side of the bell curve. So you have to roll quite high to get anywhere, and then I noticed as I put just one or two points into a skill, I would climb the bell curve and then suddenly, kind of overnight with just one or two points, I would go from this skill difficulty being really hard to this skill difficulty being actually like, not trivial, but it’s like oh okay, I can actually do that. And so I liked the way that bell curve gave me this feeling of this skill check is hard and difficult and crunchy, switching over to oh, actually no, I can do this. I’m going downhill now.

James: So that was one sort of change. Another was that I… Citizen Sleeper has just Energy and Condition, and I knew that I could replace Condition with Stress, which is kind of borrowed from Blades in the Dark, because I knew that, okay, you’re a soldier, it makes sense that you had PTSD from the war and I can make that stress go up every night because you have nightmares, so that seemed like a natural kind of parallel. And I knew that I should still have something like Energy because I knew that that short-term goal of always feeding yourself worked really well. But, I eventually realized that it’s a game about dealing with people in violent gangs and fighting against fascist soldiers and stuff, so I knew that I needed a Health stat. And then I knew, well it makes sense that rather than having when Energy is at zero and you lose more, rather than that increasing Stress that can just take off from your health. That felt very natural.

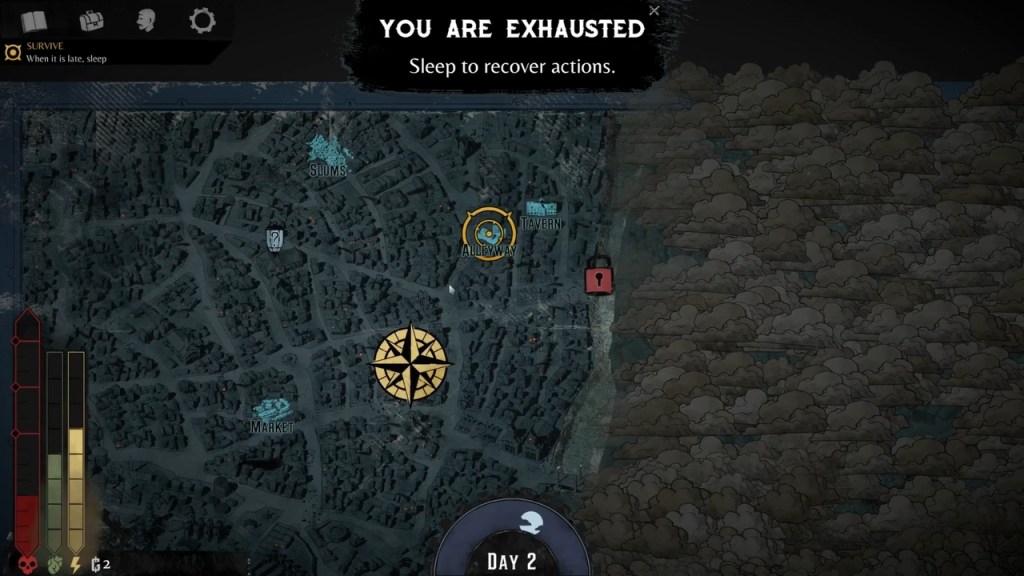

Another kind of big change is that I decided to add a day-night cycle as well. So you have four actions every day and then, when you’re done with those, it flips over and you have four night actions. I added that basically because when I play games like Skyrim, for example, I always like to install a realism mod, where you have to eat and sleep regularly, because I felt that that really helped with the immersion. I thought if the thing that made me love Citizen Sleeper was that, that kind of daily grind of having to keep yourself fed, why can’t I lean into that a bit more? And then, it effectively doubles the amount of actions that you have access to in the game generally because every location has day actions and night actions. So that means you can work in the factory during the day and make money, but then at night you can steal from the factory and it feels different. So I thought that was kind of a nice addition that also made it feel like you were actually living in the world.

One of the other major changes is that whereas Citizen Sleeper has a fairly limited number of inventory objects, but I thought I wanted more, because I was used to that from Fallen London, and it also felt that this sort of weird steampunk world should have lots of things to interact with, lots of items to acquire and items that can be turned into other items if you know the right people. Figuring out how to turn what you have now into a better future for yourself is kind of a core mechanic of the game. So if you’ve got some scrap metal, it’s like okay scrap metal, whatever, but if you can turn that into a device, which is a much more refined version of that, and then you can sell that device or you can use it somewhere. That sort of piecing together was quite integral to my mission. I always liked the idea that you’re in a city where the city provides you with everything you need to survive if you can only figure out how it all fits together. The only problem is that the people ruling this city would prefer that you die. But the city itself gives you everything if you can just make the right connections.

Drop your thoughts!