My favorite thing about reading and writing poems is that it often feels like discovering a familiar but alien language, or re-learning one you studied years ago but lost at some indiscernible time. The range in approaches allows for significant freedom in how authors express themselves. The content and construction of words, the reading experience as your eyes travel the page, the ease of adding notes in the margins so long as you have a pencil and a thought. Several elements come together to create unique portraits of relatable experiences that readers can chew on. Reading my favorite poems feels interactive, which is why I found myself thinking about them when playing Thirty Flights of Loving.

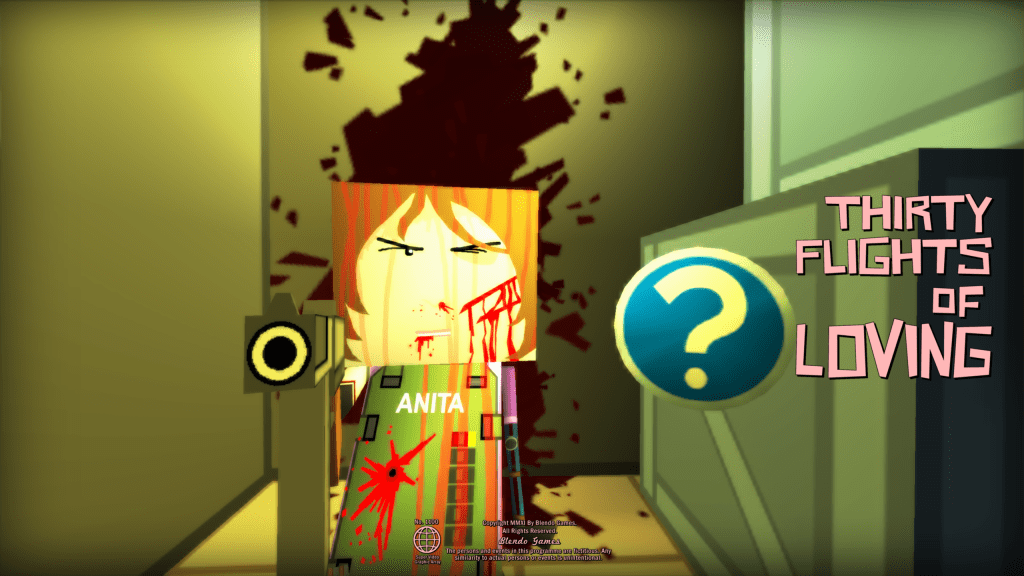

Brendon Chung’s 2012 game was brought to my attention by a Polygon article sharing Steam Spring sales. When I saw it was less than 5 dollars and about 15 minutes, I figured why not. One way to describe the game is you walk through disjointed, fast-paced scenes of a heist gone wrong. Another way is you experience a cold plunge into a world of sophisticated plans that fail spectacularly, because such stories, of drama and action and espionage and love, are often convoluted, long prepared, and quickly finished by nature. In Thirty Flights of Loving’s case, the delivery decided to reflect its content almost to a T. There is no easy explanations given as one scene interrupts another, all still connected but asking you to determine the meaning and connect the dots. When the game came to a close, I thought to myself, “It feels like I played a poem.”

But then, I played through the director’s cut version for my second playthrough, and discovered the developer often built games around music. While he noted the process was different for Thirty Flights of Loving, I realized my experience actually resonated with this angle more. While there are a few differences between how I listen to music versus reading a poem, the one to highlight here is how I go about first impressions of a work.

With poems, I do like to read through it once entirely, but even in that process my eyes are catching words down the page or jumping back to the start of a sentence. While the more in-depth scrutinizing happens after the full read is done, a poem is presented to me either in its entirety or in large parts from the moment I lay eyes on it. Past a title and its author, I can still spot the line breaks, the space taken and ignored on a page. I may not know what they mean yet, but a part of itself is revealed nonetheless. Plus, I’ll admit to stopping in the middle of some first-reads because I can’t help poring over a striking word or line. The nice thing about poems is that they wait when you stop and stare. Not wholly, but at least in part.

I do not and cannot have the same process with a song. My first time with a piece of music is a ride I let myself get strapped into and put my hands in the air for. Stopping at all feels wrong. I could pause a swinging ship, or a mounting coaster, at its apex and take in the view, but to what end? What is a ride when it’s not in motion, if not considered broken? For as flow-y as poems and similar writing are often thought to be, my first moment with a printed word is often held easier than music. The latter becomes a memory quicker. It’s being chased but rarely caught, even in its constructed moments of stillness or release from climax.

While I literally need to keep my hands on the mouse and keyboard to keep the ride called Thirty Flights of Loving going, my initial experience with it matches my first-time music listening habits best. Even if I were to get lost or stop moving, the surrounding environment is often, if not always, feeding me noise. I will always appreciate and prefer the pause button’s availability, but I like to save its use for emergencies in games like these. To pause music feels like missing the point of it, and that’s where I land with Thirty Flights of Loving. It’s best experienced when uninterrupted.

Drop your thoughts!